Are Reflex Sights Worth the Cost?

A quick look at any modern firearm and you’ll notice something: optics. Modern rifles may not even come equipped with iron sights. Pistols aren’t long for that change either. Many models are being released with an optics platform attached. Popularity doesn’t always mean performance though.

While old irons are still the tried-and-true method for some, the past 20 years plus of conflict has taught many U.S.-based companies that it’s time for an upgrade. This conversation could dive deep into different sight heights, dot and picture colors, a discussion about batteries and the differences between dot and holographic. The primary element at play though is one shooter skill: Sight Picture.

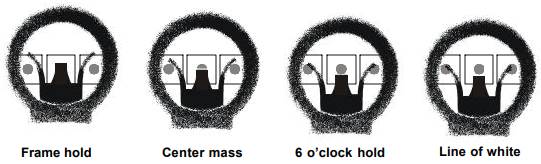

The sight picture that many veteran shooters will be familiar with is what’s commonly known as “lollipopping” or a 6 o’clock hold. Using iron sights on either a rifle or pistol, the shooter aligns the sights and places them just beneath the desired target, thus “lollipopping” the target with the front sight post. The theory is that while maintaining focus on the front sight this hold offers the best compromise of options. This places the point-of-aim lower than the point-of-impact.

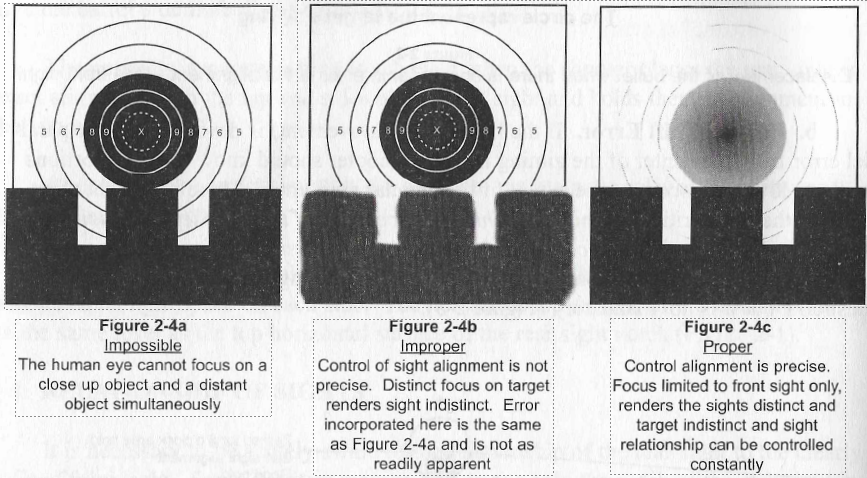

Shooters can maintain a combination of target awareness, the front sight, and the rear sight in the sight picture. Based on traditional bullseye shooting, focus zeroed in on the front sight allows a three to six-second window of alignment to cleanly break a shot.

Proper alignment and focus with iron sights only allows for some attention on target.

Educational Figure from the Army Marksmanship Unit

Source: Service Rifle Marksmanship Guide

As methods of teaching developed, military shooters were taught similar methods to bullseye and long range shooting.

Those traditional teaching methods are ingrained in our shooting culture now. They were taught to tactical level users even though three to six seconds seems an eternity on a battlefield. They made the assumption that a majority of targets would present between 50 and 300 meters, emphasizing accuracy over speed.

Current U.S. Army rifle qualification uses targets from 50 to 300 meters.

Source: DoD

All of that history and sight picture jargon amounts to one thing…a way to see what you’re shooting and be able to consistently align the point-of-aim and the target. But there are two major issues with these classic techniques.

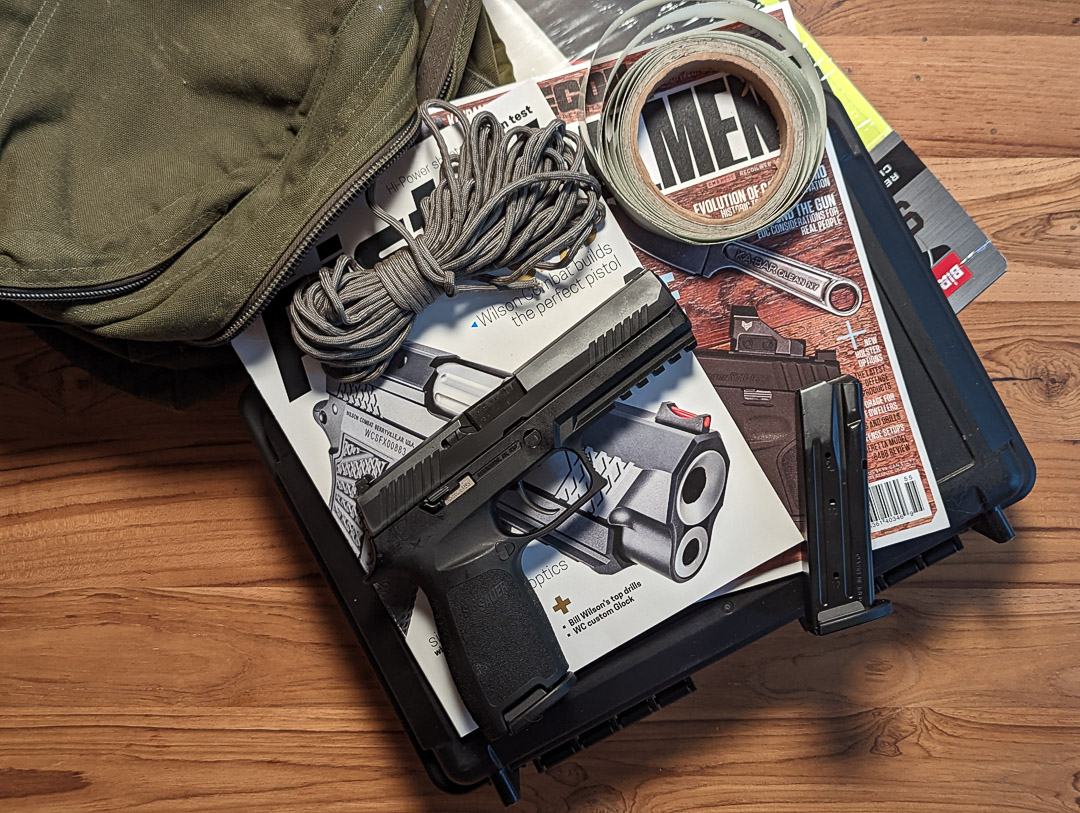

Source: Kinetic Staff

First is where a shooter is focused. While shooting plates or bullseyes a shooter can focus on the front sight rather easily. Admittedly, doing just that will improve accuracy drastically for a new shooter. So much so that all manner of highlights, whiteout, and even fiber optics are applied to front sight posts.

The problem comes when the target is no longer stationary, say in the event of an assailant or enemy on the battlefield. While some shooters have taken the years it requires to fall naturally into refocusing on their front sight, most have a tendency to immediately look at the threat.

Front sights started to adapt to help pull in the users focus, but haven’t changed much otherwise.

The second problem is speed. Even with years of practice, whether on a rifle or pistol, aligning those sights properly isn’t a process that lends itself to speed. If a shooter has already shouldered or presented the weapon or is transitioning targets, they may be rather quick to realign and fire. Compared to firing from a holster or the low ready though, most shooters can’t align quickly.

These two problems are what lead to a majority of military and law enforcement users focusing on optics or not even using a sight picture. Backplate or reflex shooting became a popular training tool to increase speed, as did the Aimpoint or ACOG mounted on most military weapons.

Optics-based sight pictures appeal to the lowest common denominator among shooters. While years of practice will eventually lead to a better shooter, the optic-based approach allows even a relatively new shooter to have one less fundamental to worry about.

Most, if not all, active duty units utilize optics on their primary weapon.

Source: DVIDS

Optics-based sight pictures appeal to the lowest common denominator among shooters. While years of practice will eventually lead to a better shooter, the optic-based approach allows even a relatively new shooter to have one less fundamental to worry about.

Now, there are plenty of arguments against these points. Most revolve around proper training, slowly increasing pace, consistent shooting, and good habits or muscle memory. The sight picture forces slower, more deliberate training and emphasizes diagnosing a shooter’s mechanical problems before simply cranking away on an adjustment dial.

Most, if not all, of the arguments in favor of iron sight shooting harp on these fundamentals and require years of practice. Years well spent.

That said, as soon as target engagement under that three-second mark comes into play, those fundamentals transfer really well to an optics-based sight picture. The “point and shoot” visual doesn’t necessarily erase good mechanics but does allow for (slightly) greater speed for most shooters.

Both these considerations are tactical. Not all shooters are, or should be, considering their shooting habits from a tactical perspective. Bullseye shooting, most hunting, and general plinking with friends should be more deliberate and emphasize safety and good mechanics over imagined scenarios. But you’d be hard-pressed to deny that optics give a marked advantage to tactical shooters.

By allowing a center of mass hold, better visibility of the target, and removing the natural complexity of aligning a front and rear sight, red dots and reflex sights on both rifles and pistols allow for quick target engagement, easier situational awareness, and critical to this conversation – a simpler sight picture.

Source: Swampfox Optics

Center mass hold, with a red dot and with iron sights.

There’s also one last shooting scenario that seals the deal in most respects. Shooting at night. Developments in technology for low light shooting take a simple advantage in the day and turn it into a complete overmatch. Even without night vision, the ability to simply see an electronic dot and know that it’s on target in low light can be the difference between deliberately firing or simply trying to suppress a threat.

At night, an optic can be the difference between a hit and a miss.

Source: DVIDS

So are reflex sights or red dots worth the cost? The real answer: it depends. If a shooter’s primary purpose is bullseye or sport shooting, they’d probably be better off learning fundamental shooting habits with iron sights. As soon as speed or tactical advantage are needed though, transferring those basic fundamentals to an optic is probably the right way to go.